How to avoid time anxiety in graduate school and academia by scheduling and time blocking

Before I finished my dissertation, I felt overwhelmed by the time pressure to complete it while simultaneously working on other projects. I was in a “freeze” mode, finding it difficult to start my day and to continue working once I mustered up the energy to start. God forbid, if I took a break during a work session, it was doubtful that I’d find the energy to restart. Instead, I often morphed into my couch after lunch breaks, incapable of dragging myself back to my desk. I felt heavy from the fear of not submitting passable work, being late, or the worst-case scenario — finishing late and failing. For a while, the pressure of finishing the dissertation left me making minimal progress and feeling frozen. Luckily, with problem-solving and a good plan, stress-induced freeze states can be melted and get you back in motion.

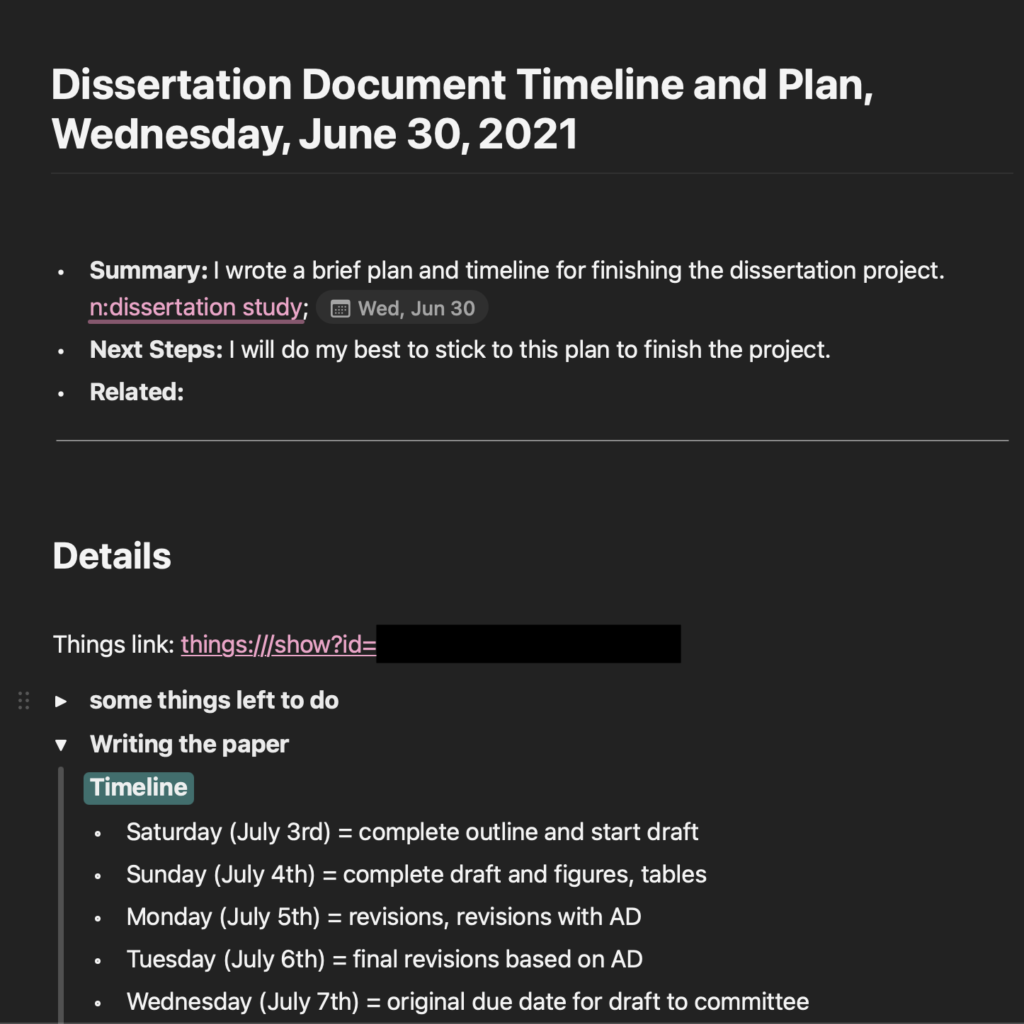

Brian King, behavioral neuroscientist and author of The Art of Taking It Easy: How to Deal With Bears, Traffic, and The Rest of Life’s Stressors, affirms that making a detailed plan to solve a problem helps prevent stress. He encourages readers to evaluate problems that seem overwhelming and determine if they are actually “bears”, or something serious enough that could cause fatal harm. We have to change our mindset about daily stressors. If we view them as interesting challenges instead of insurmountable feats, we can learn to have fun with whatever gets thrown at us. After I sat down and made a detailed outline of the rest of my time in graduate school (see example below; made with Craft Docs), I felt a stronger sense of direction. Since finishing my PhD, I use a combination of planning strategies to manage my work, including (1) the weekly plan, (2) the daily plan, and (3) the annual+ vision.

A Word of Caution About Planning

Before I jump into my planning system, let’s be clear about one thing: there is no perfect planning system. The system that I will explain below was developed from several iterations and has been informed by many books, blogs, podcasts, conversations, subreddits, slack threads, and YouTube videos. My system is still imperfect and still evolving. That is to be expected. Any planning strategy should evolve with you to meet your current needs. The following method is an example of the system that I currently use to plan my academic work as a postdoctoral research scientist.

The Weekly Plan

“At the beginning of every day, mentally fast-forward to the end of the day, and ask yourself: When the day is over, what three things will I want to have accomplished? Write those three things down. Do the same at the beginning of every week.” – Chris Bailey, The Productivity Project: Accomplishing More by Managing Your Time, Attention, and Energy

Each week, I sit down with my bullet journal to outline my intentions. Similar to Chris Bailey’s rule, I limit my intentions to a maximum of three. These are the big picture projects or intentions that I want to work towards throughout the week. Using these intentions, I plan individual tasks that relate to them. Each task that makes it to my weekly to-do list is based on the intentions for the week.

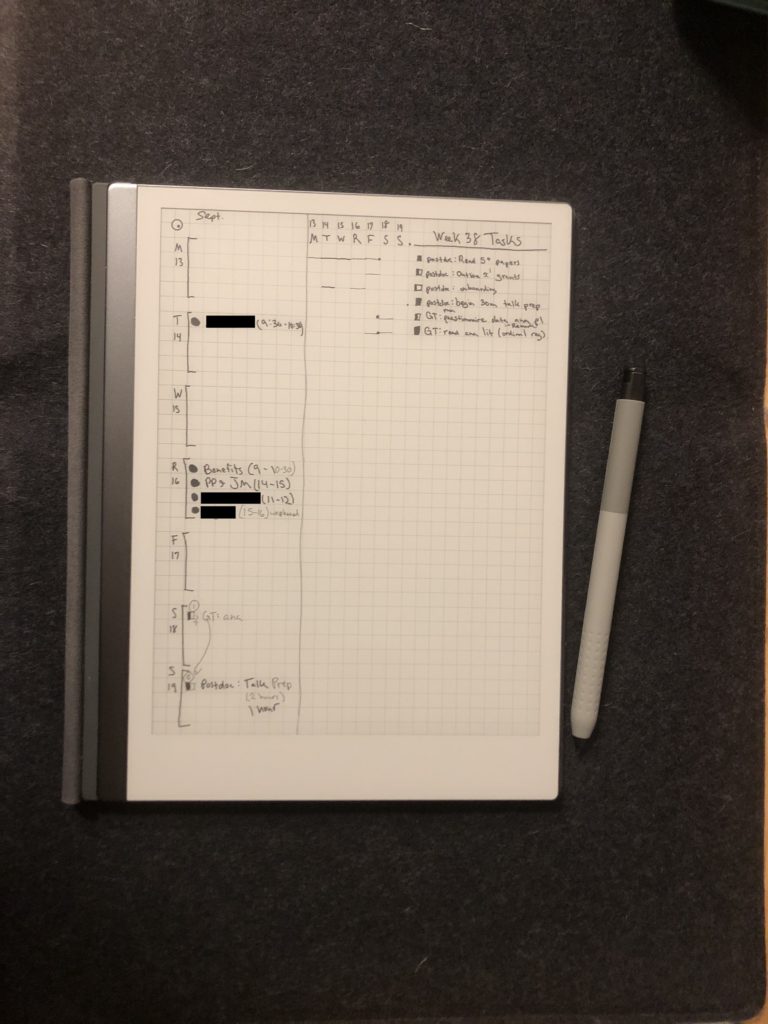

I list my tasks using the “rolling weekly” method (see video here; example shown below). The rolling weekly is a bullet journaling method that allows for tasks to be carried from day to day. There are often things that can’t be completed in a single day, and visually representing a timeline with the rolling weekly helps facilitate multi-day tasks and visualize progress.

In a column next to the rolling weekly, I list Important events for the week (example above). This gives me a visual of how much time is dedicated to scheduled events on any given day. Having this framework helps me see what days allow for the most individual work and what days are dominated by meetings or other scheduled events.

Once the week is over, I do a quick review to briefly reflect on my weekly intentions, specifically regarding how well I worked on them. This helps me to make any necessary adjustments to my system and prepare for the week ahead.

The Daily Plan

The weekly plan informs what I schedule for each day. In the mornings, I select tasks from my weekly list to work on during the current day. For each day, I set a clear intention for what I want to have accomplished by the end of the day.

“It does no good to create a to-do list that requires five hours of work if you only have three hours available to you. Doing so will set yourself up for failure.” – Damon Zahariades, To-Do List Formula: A Stress-Free Guide To Creating To-Do Lists That Work!

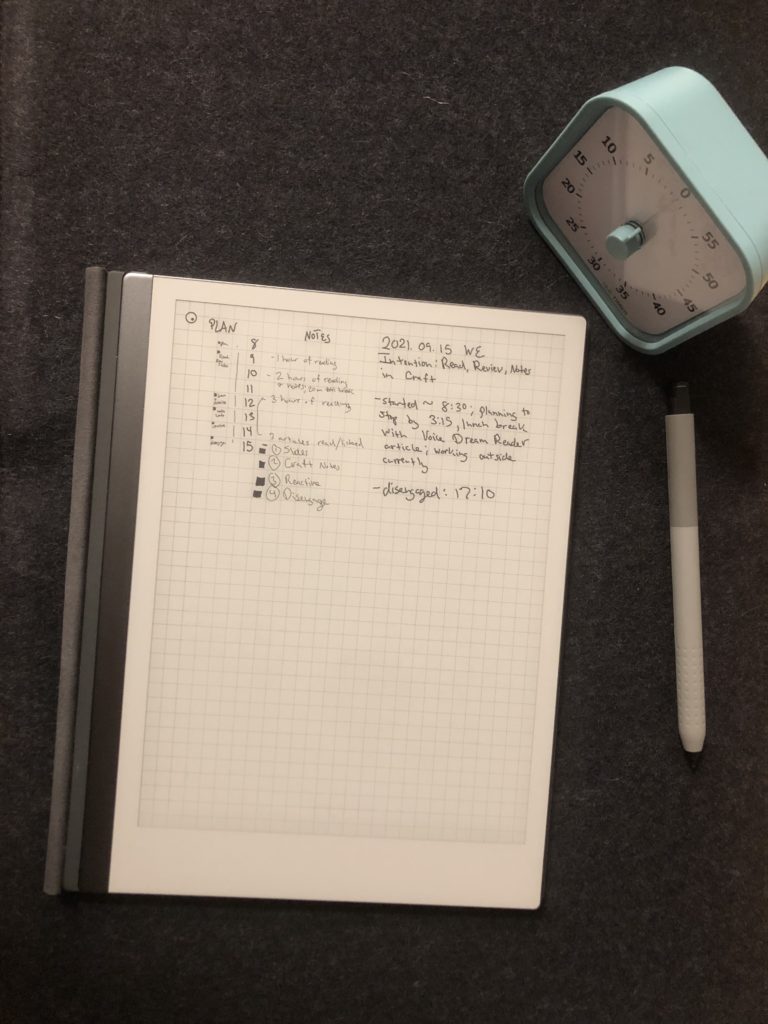

The most important aspect of my daily plan involves my time blocking system. My design for time blocking is simple (see example below; see Cal Newport’s method here). It consists of a linear column of each hour. To the left of the listed times, I outline scheduled events for the day (e.g., meetings, talks, workshops). Then, I schedule focused work blocks around those pre-scheduled events. On the right, I save space for notes about deviations or revisions to my plan.

At the end of the workday, I do a quick disengagement (see Cal Newport’s daily shutdown routine here). I clear my inboxes, take notes, and review my day.

One of the most critical aspects of my disengagement process is to clear my task list. The goal is to finish what I’ve scheduled for myself. Damon Zahariades warns that “failing to complete your to-do items day after day, [trains] your mind to accept that outcome.” As someone who is sometimes overly ambitious, I don’t always complete my to-do list. When that happens, I make sure to reschedule tasks for a more appropriate time. My inboxes are often a direct reflection of my mental state. Clearing my email inboxes and daily task list at the close of each day helps me to clear my mind, disengage from my work, and relax.

The Annual+ Vision

For the year of 2021, I planned annual themes (see Cortex podcast on annual themes here) and a vision for what I want for my life. This isn’t necessarily a plan, but it helps me to consolidate my values and stay true to those values in every aspect of my life. This is the foundation for how I spend my time. If something does not align with my core values, it gets no place on my schedule. Time is invaluable. We cannot afford to waste it.

Intentionality Leads to Time Well Spent

Graduate students and academics are always expected to be in motion. It can feel like a rollercoaster ride that never stops. It has lulls and chaos, hills and valleys, ups and downs, and it can be difficult to get a chance to stop and think about what we should be doing and when exactly we should be doing it. Effective time management comes from being deliberate about how we decide to schedule tasks and spend our time. Notably, making the plan is only a small part of the battle. After the plan is made, it has to be consciously and intentionally executed. I am certain that you can reach your goals with intentional planning, scheduling, and unrelenting execution.

Enjoyed this post and want to say thanks?